By providing exemptions for religious properties, publications, and other related materials and activities, legislatures have sought to encourage the beneficial secular effects of religious organizations while avoiding First Amendment–based concerns of excessive government entanglement and establishment of religion. For the courts, navigating the religion clauses of the First Amendment has proved challenging. In this photo, the Rev. Jerry Falwell speaks at his Thomas Road Baptist Church in Lynchburg, Va., Oct. 24, 1999. Falwell filed a federal lawsuit against the state of Virginia and the city of Lynchburg, Friday, Nov. 9, 2001, to challenge longstanding laws that prohibit churches from incorporating and limit the amount of tax-exempt land churches can own. (AP Photo/Stephanie Klein-Davis)

Both before and after adoption of the Bill of Rights, state legislatures enacted, and the courts upheld, tax exemptions for religious entities, which are generally shared with charities. The federal legislature from its earliest days has exempted religious entities from the national tax base. Today, in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, statutes and constitutions provide various types of property tax exemptions for religious organizations. Similarly, the federal government has exempted churches and other religious organizations from federal taxation in the modern federal tax code since ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1913.

By providing exemptions for religious properties, publications, and other related materials and activities, legislatures have sought to encourage the beneficial secular effects of religious organizations while avoiding First Amendment–based concerns of excessive government entanglement and establishment of religion. For the courts, navigating the religion clauses of the First Amendment has proved challenging.

In Walz v. Tax Commission of the City of New York (1970), Frederick Walz, a property owner in New York, sought an injunction to prevent the New York City Tax Commission from granting statutorily permitted tax exemptions on property used solely for religious purposes. He argued that such exemptions provided a financial benefit to religious organizations in violation of the First Amendment’s establishment clause. The Supreme Court, in an 8-1 plurality decision written by Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, held that tax exemptions for property owned by religious organizations and used solely for religious worship did not violate the establishment clause.

The Court held that although the establishment clause prohibits government from sponsoring or actively involving itself in religious activities, it may permissibly operate with “a benevolent neutrality” that allows religious organizations to exist without sponsorship and without interference. The Walz Court similarly found that the exemptions administered by the New York City Tax Commission caused no “excessive entanglement,” only a “minimal and remote involvement” between church and state.

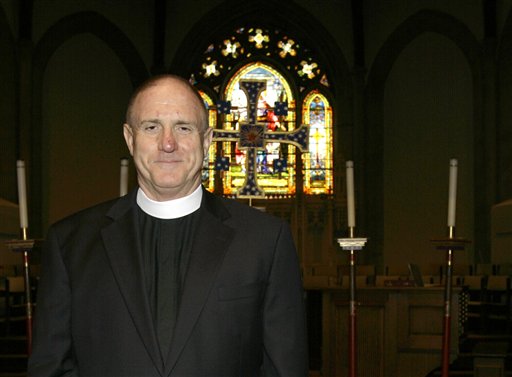

In recent years, the Internal Revenue Code sec. 501(c)(3), which prohibits tax-exempt organizations, including religious entities, from engaging in campaign activities has garnered increased public attention. In this photo, the Rev. Ed Bacon is photographed at All Saints Church in Pasadena, Calif., Wednesday, Sept. 20 , 2006. The liberal church was locked in an escalating dispute with the IRS over an anti-war sermon — delivered two days before the 2004 presidential election — that could cost the congregation its tax-exempt status. (AP Photo/Nick Ut)

Chief Justice Burger would draw upon the Court’s prior establishment clause cases, including Walz, when the Court announced a new test in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) to decide when governmental actions violated the establishment clause. According to the Court’s three-part Lemon test, to be consistent with the establishment clause a statute must

In Texas Monthly Inc. v. Bullock (1989), the U.S. Supreme Court applied the Lemon test to consider the constitutionality of a Texas statute that granted a tax exemption specifically to religious periodicals. Unlike the property tax exemption at issue in Walz, which extended benefits to a broad class of nonreligious entities in addition to religious groups, the statute in Texas Monthly was narrowly drafted to benefit religious organizations alone. In a 6-3 plurality decision, the Court held that the Texas statute failed the Lemon test in that it

In recent years, the Internal Revenue Code sec. 501(c)(3), which prohibits tax-exempt organizations, including religious entities, from engaging in campaign activities has garnered increased public attention. For example, in Branch Ministries v. Rossotti (D.C. Cir. 2000), the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit upheld the Internal Revenue Service’s revocation of the tax-exempt status of a church that had engaged in political campaign activity, in violation of the Johnson Amendment, which prohibited such churches from endorsing political candidates.. Although this issue has prompted much comment in both the media and Congress, neither Congress nor the courts have altered the rule.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2020. Joseph Rosenblum is a Colorado attorney.